NVH-Optimierung und Produktions-Toleranzen

In der heutigen Getriebeentwicklung gewinnen Ressourceneffizienz und Umweltschonung, insbesondere die Minimierung des CO2-Fußabdrucks, zunehmend an Bedeutung. Diese Faktoren sind entscheidend, um gesetzliche Grenzwerte einzuhalten und angesichts einer stetig wachsenden Konkurrenz auf dem Markt wettbewerbsfähig zu bleiben. Damit Getriebehersteller diesen Anforderungen gerecht werden, steigern sie die Leistungsdichte der Getriebe kontinuierlich. Dies erfordert eine sorgfältige Analyse und Reduktion überschüssiger Materialreserven, um eine optimale Effizienz zu gewährleisten. Ziel ist es, die Getriebe mit möglichst langer Lebensdauer und einem ruhigen, vibrationsfreien Betrieb, sprich guter NVH-Performance, auszulegen.

Entwicklungsprozess

Die Entwicklung von Getrieben ist ein iterativer Prozess, der oft mehrere Design- und Testzyklen umfasst, um die gewünschten Leistungsparameter zu erreichen. Moderne Simulationsmethoden spielen dabei eine zentrale Rolle, da sie es Ingenieuren ermöglichen, virtuelle Prototypen zu erstellen und das Verhalten von Getriebesystemen unter verschiedenen Betriebsbedingungen vorherzusagen. Dies verkürzt nicht nur die Entwicklungszeit erheblich, sondern trägt auch zur Kosteneffizienz des Entwicklungsprozesses bei. Bewährte Softwaretools wie die FVA-Workbench [1] verbessern den Konstruktionsprozess durch schnelle und zuverlässige Simulationen.

Analyse und Optimierung

In der Getriebeentwicklung ist es wichtig zu wissen, welche Einflüsse auf das Getriebe wirken und welche Belastungen daraus resultieren. Dabei spielt die genaue Kenntnis der sich im Betrieb ergebenden Breitenlastverteilung [2] in den Zahneingriffen und deren Optimierung durch geeignete Mikrogeometrien eine entscheidende Rolle.

Lastbedingte Verformungen und Verlagerungen in Getrieben können zu erheblichen Schiefstellungen in den Verzahnungseingriffen und damit zu einem ungleichmäßigen Breitentragen führen. Eine ungleichmäßige Lastverteilung über der Flanke ist nicht nur schädlich für die Lebensdauer, sondern verschlechtert auch die Geräuschanregung [3]. Um dies zu vermeiden, sind Verzahnungskorrekturen so auszulegen, dass Verformungen kompensiert werden, also eine flächige und gleichmäßige Pressungsverteilung ohne Spannungsspitzen erreicht wird. Das führt zu geringen Steifigkeitsschwankungen des Zahneingriffs und dadurch zu geringeren Verzahnungsanregungen in Form von Drehwegfehlern. Dazu ist eine detaillierte Betrachtung aller Getriebeverformungen notwendig.

Verzahnungsmodifikationen sind, wie andere Fertigungsparameter auch, streuungsanfällig. Was im Idealfall der Nennlast und Nenngeometrie eine gute Auslegung zeigt, kann aufgrund von Toleranzen im fertigen Bauteil weniger optimal sein. Vor allem Winkelkorrekturen unterliegen einer erheblichen Varianz. Daher ist nicht nur eine gute Nenngeometrie, sondern auch eine robuste Auslegung von entscheidender Bedeutung. Wie die Robustheit der Auslegung bewertet werden kann, wird im folgenden Beispiel gezeigt.

Berechnungsbeispiel

Im folgenden Berechnungsbeispiel wird anhand detaillierter Getriebesystemanalysen mit der FVA-Workbench gezeigt, wie zunächst automatisch eine Grundauslegung der Flankenmodifikationen durchgeführt und anschließend mittels einer Kennfeldgenerierung mit variierenden Flankenmodifikationen der Toleranzeinfluss aus der Fertigung berücksichtigt wird. Auf diese Weise lässt sich eine, für den jeweiligen Anwendungsfall, optimale und robuste Auslegung ermitteln.

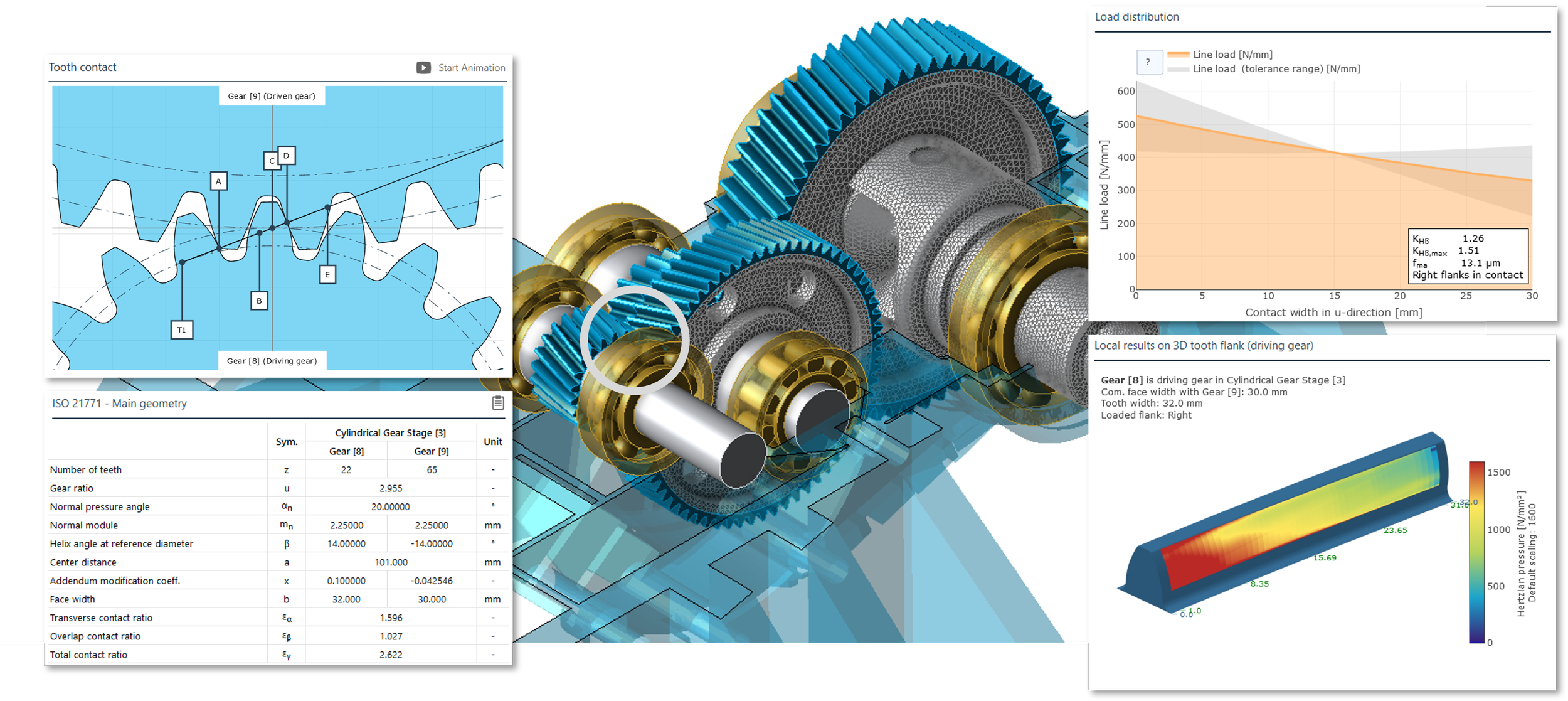

Als Beispielmodell wird hier ein Reduktor Getriebe eines elektrisch angetriebenen PKWs verwendet (s. Abbildung 1). Um sämtliche Steifigkeits- und Kreuzeinflüsse exakt zu berücksichtigen, die sich auf den Zahneingriff und die Breitenlastverteilung auswirken, wurden neben der Modellierung der detaillierten Stirnradstufen und dem Welle-Lager-System auch das Getriebegehäuse, die Radkörper und der Differentialkorb als FE-Komponenten ausgeführt. Das Modell beinhaltet zudem Halterungen am Getriebegehäuse, da das Getriebe auf einem Prüfstand getestet wurde.

Abbildung 1: Zweistufiges Reduktor Getriebe in der Auslegung ohne Flankenmodifikationen

In der FVA-Workbench lassen sich maßgeschneiderte Massenrechnungen und Auslegungen mit Hilfe von Skripten durchführen. Diese einfach anwendbare Skriptsprache ermöglicht es, umfangreiche Studien automatisiert zu berechnen. So lassen sich sämtliche Parameter eines Modells definieren, Berechnungen durchführen und Ergebnisse herauslesen und ausgeben, beispielsweise in Excel.

Sollten häufiger umfangreiche Berechnungsstudien in der Entwicklung notwendig sein, bietet es sich an Massenrechnungen zu parallelisieren, um die Rechenzeit zu reduzieren. Dafür eignet sich eine Serverlösung, wie der FVA SimulationHub, am besten. Die Serverlösung ermöglicht es, Berechnungsaufträge auf beliebig vielen Instanzen auf dem Server berechnen zu lassen. Die Zeitersparnis mit dem SimulationHub ist linear skalierbar, d.h. zwei Instanzen halbieren die Rechenzeit.

Automatische Grundauslegung der Flankenmodifikationen

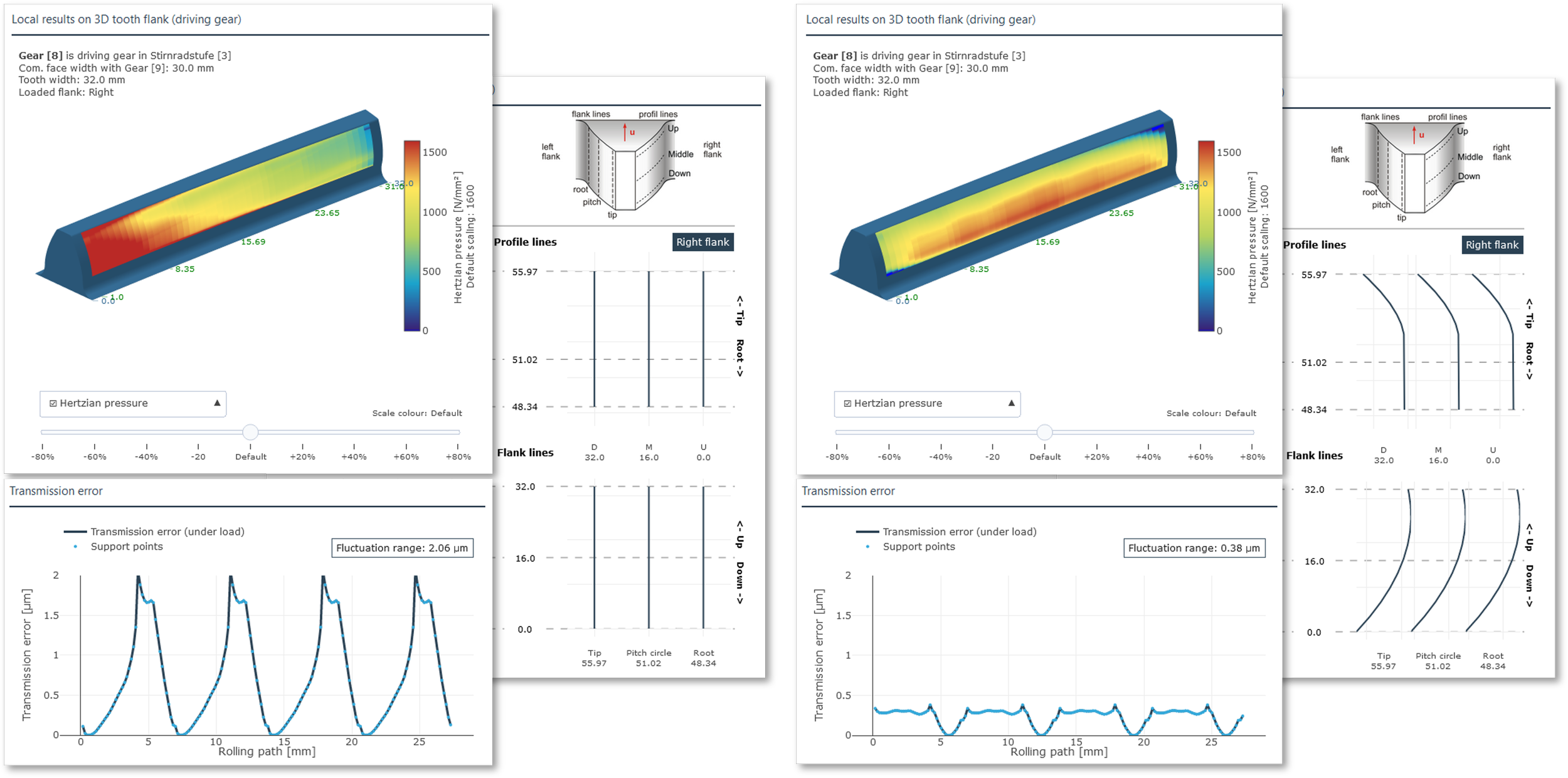

Für eine erste Grundauslegung der Flankenmodifikationen aller Stirnradstufen im Getriebe wird ein vorgefertigtes Skript in der FVA-Workbench verwendet, dass das Getriebe im ersten Schritt ohne Modifikationen berechnet, den Kontakt und die Breitenlastverteilung analysiert und dann im zweiten Schritt empfohlene Modifikationen berechnet, wie Kopfrücknahmen nach Sigg [4] und eine Schrägungswinkelkorrektur für ein mittiges Tragbild. Diese werden im Modell integriert, simuliert und ein direkter Vergleich des Zahneingriffs und der Verzahnungsanregung mit und ohne Modifikationen ermöglicht (s. Abbildung 2).

Abbildung 2: Ergebnis der automatischen Grundauslegung der Flankenkorrekturen auf die Kontaktdruckverteilung des Zahneingriffs und den Drehwegfehler, ohne Modifikationen (links) mit Modifikationen (rechts)

Diese erste automatische Auslegung resultiert bereits in einem mittigen Zahnkontakt mit niedrigeren Spannungen und ohne Spannungsspitzen an den Rändern des Kontakts, was zu deutlich geringeren Schwankungen führt.

Die Schwankungen des Drehwegfehlers lassen sich nicht direkt mit unterschiedlichen Zahnraddesigns und anderen Getrieben vergleichen, da die unterschiedlichen Zahnsteifigkeiten den Drehwegfehler beeinflussen. Alternativ kann die Schwankung der Zahnkräfte und daraus der Anregungspegel berechnet werden. Dieser ermöglicht einen qualitativen und quantitativen Vergleich verschiedener Stirnradstufen und Getriebe.

Parameterstudie zum Einfluss der Fertigungstoleranzen

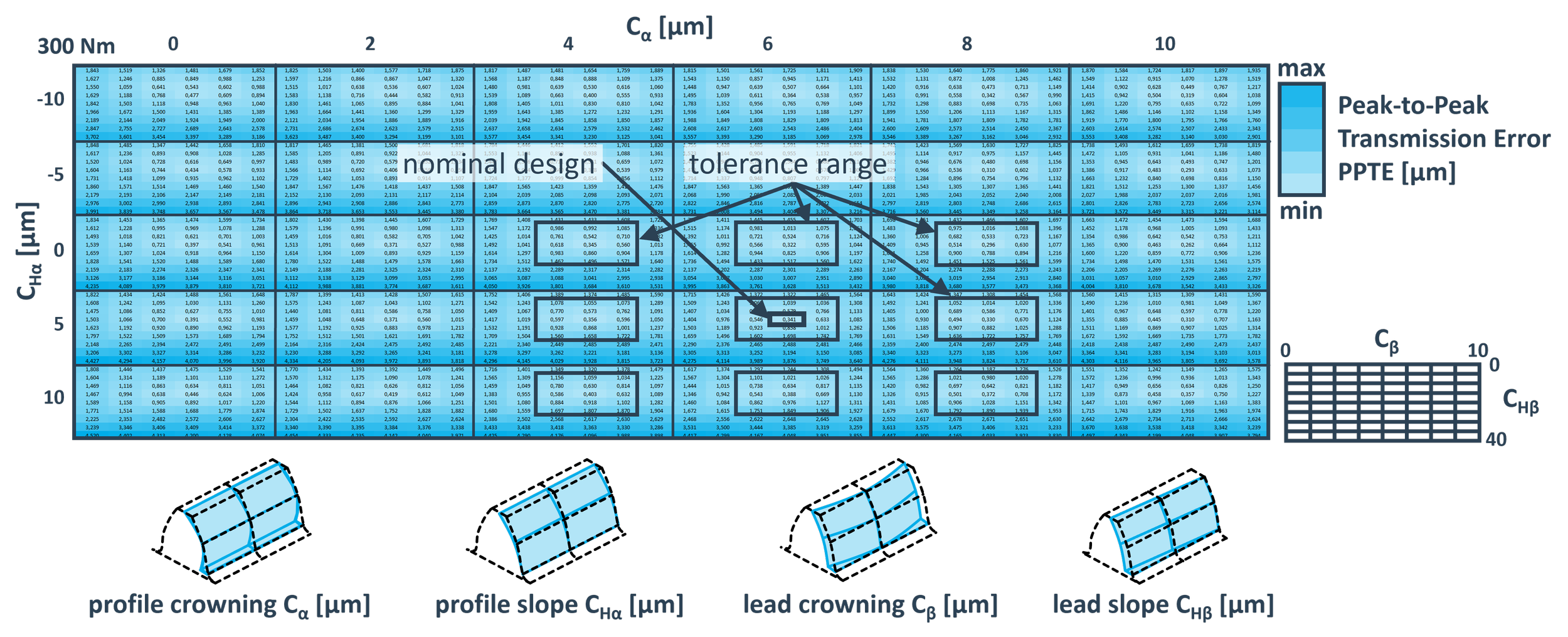

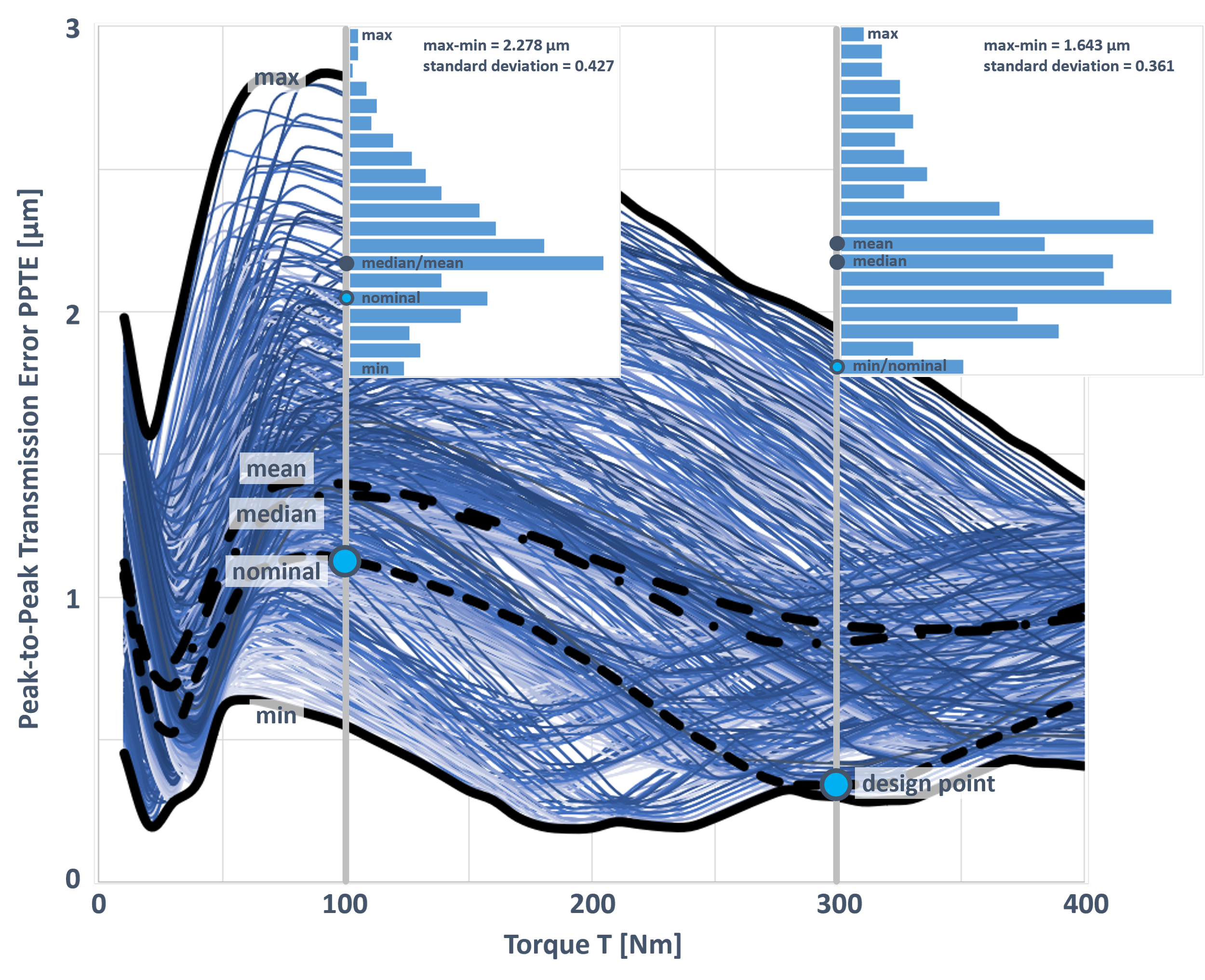

Bei einer weiteren Studie wird ein Kennfeld des Drehwegfehlers ermittelt für unterschiedliche Drehmomente T und Variationen der vier Flankenmodifikationen: Profilwinkel CHα, Profilballigkeit Cα, Flankenwinkel CHβ, Flankenballigkeit Cβ (s. Abbildung 3 und Abbildung 4). Dadurch lässt sich ermitteln, ob die nominelle Auslegung der Flankenmodifikationen auch über das fertigungsbedingte Toleranzfeld robust niedrige Verzahnungsanregungen aufzeigt.

Abbildung 3: Drehwegfehler bei 300 Nm Drehmoment für vier variierte Parameter zur Auslegung der Flankenmodifikationen

Aus allen Ergebnissen des Toleranzfeldes werden die minimal und maximal auftretenden Drehwegfehler ermittelt und die Standardabweichung berechnet als Maß für die Robustheit der Auslegung.

An dem gezeigten Beispiel sieht man, dass die Auslegung der nominellen Flankenmodifikation bei 300 Nm Drehmoment zu sehr niedrigen Drehwegfehlern führt. Berücksichtigt man jedoch die Fertigungstoleranzen, dann liegen die meisten Ergebnisse bei deutlich höheren Drehwegfehlern, obwohl die Toleranzen der vier Eingabeparameter symmetrisch zum nominalen Design sind. Bei 100 Nm Drehmoment ist der Drehwegfehler des nominalen Designs wesentlich größer und liegt deutlich näher am Mittelwert aller Ergebnisse des Drehwegfehlers. Ohne eine detaillierte Toleranzuntersuchung kann man deren Auswirkungen nicht vorhersagen. Zudem muss in solchen Fällen mit deutlich höheren Sicherheiten gearbeitet werden, was das Design größer, schwerer und teurer macht.

Abbildung 4: Drehwegfehler aller Variationen im Toleranzbereich über dem Drehmoment, Häufigkeitsverteilung für 100 und 300 Nm.

Fazit

Die FVA-Workbench ermöglicht eine einfache, schnelle und detaillierte Berechnung komplexer Getriebe. Dabei werden sämtliche relevanten Details des Gesamtsystems berücksichtigt, deren Steifigkeit und Verhalten potenziell den Zahneingriff beeinflussen könnten. Durch gezielte Flankenmodifikationen kann das Tragbild optimiert werden, was zu reduzierten Spannungen, einer längeren Lebensdauer und einem vibrationsarmen Eingriff führt – sprich, zu einer ausgezeichneten NVH-Performance.

Flankenmodifikationen können unter Betriebslast nominell zu einem herausragenden Design führen. Doch wenn der Einfluss toleranzbehafteter Fertigung nicht berücksichtigt wird, birgt dies ein signifikantes Risiko für die Produktion minderwertiger Getriebe. Diese könnten als Ausschuss aussortiert oder nachgearbeitet werden müssen, was zu erhöhten Produktionskosten, Unzufriedenheit bei den Kunden und Beeinträchtigungen der Wettbewerbsfähigkeit führen kann.

Durch die FVA-Workbench kann der Auslegungsprozess weitgehend automatisiert werden, sodass der Anwender sich auf die eigentliche Aufgabe, nämlich die Bewertung der Ergebnisse, konzentrieren kann. Dadurch lässt sich in kurzer Zeit ein robustes Getriebe entwickeln, bei dem das Risiko von Problemen während der finalen Umsetzung, also der Fertigung, minimiert wird. Dies führt nicht nur zu Zeitersparnis bei der Entwicklung, sondern auch zu Kosteneinsparungen, Materialverringerung und einer Reduzierung des CO2-Fußabdrucks des Getriebes.

Referenzen

[1] FVA-Workbench „Modulbeschreibung” online verfügbar unter: FVA-Workbench — fva-service.de

[2] T. Placzek, „Lastverteilung und Flankenkorrektur in gerad- und schrägverzahnten Stirnradstufen“, Technische Universität München, Institut für Maschinenelemente (FZG), München, 1988

[3] D. Mandt und H. Geiser, „ Anregungsverhalten bei Flankenkorrekturen“, FVA 338 I+II Heft 634, Frankfurt, 2001

[4] H. Sigg, „Profil- und Längskorrekturen an Evolventengetrieben“, vorgestellt auf der halbjährlichen Tagung der AGMA (American Gear Manufacturers Association) 109.16, Chicago, 1965

Autor

Dipl.-Ing. Dennis Tazir

Gear Specialist, FVA GmbH

Dennis Tazir ist ein Software-Entwickler und Simulationsexperte mit einem starken Hintergrund in der Getriebeauslegung und -analyse. Seit Februar 2020 arbeitet er bei der FVA GmbH als Software-Entwickler. Zuvor war er über sieben Jahre bei Opel als Senior Simulation Engineer für die Getriebeauslegung tätig, nachdem er zuvor ähnliche Aufgaben bei der TECOSIM Group für Opel übernommen hatte. Seine Karriere begann er als wissenschaftlicher Mitarbeiter am Fraunhofer-Institut für Betriebsfestigkeit und Systemzuverlässigkeit LBF, wo er über vier Jahre tätig war. Er hat einen Abschluss als Diplom-Ingenieur im Maschinenbau von der Technischen Universität Darmstadt (1999–2006).

Jetzt zum Newsletter anmelden

Registrieren Sie sich für unseren Newsletter, um die neuesten Informationen zu Antriebstechnik Software, White Papers und Weiterbildungen zu erhalten.

FVA-Workbench Features im Überblick

Sie möchten mehr über die Funktionalitäten der FVA-Workbench erfahren? Hier finden Sie einen Überblick über die aktuellen Features.